Erased from the Scene: Türkiye’s Withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention

Abstract

This report provides a comprehensive, in-depth examination of the political, legal, and societal impacts stemming from Türkiye's withdrawal from the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, a landmark treaty famously known as the Istanbul Convention. Hailed as the gold standard for human rights treaties addressing gender-based violence, its creation in Istanbul was a point of national pride for Türkiye. In a move that shocked the international community and human rights advocates worldwide, Türkiye, the very first nation to both sign and ratify the treaty, announced its departure by a unilateral presidential decree on March 20, 2021. This action represented an unprecedented and deeply alarming reversal in the domain of international human rights law, setting a dangerous precedent. This paper argues that the withdrawal was not a reaction to authentic societal concerns, but was instead the culmination of a calculated, politically motivated campaign. This campaign was fueled by widespread disinformation that deliberately targeted the Convention's foundational principles of gender equality and non-discrimination, misrepresenting them as threats to national values. Utilizing qualitative data gathered from comprehensive interviews with legal professionals, civil society leaders, and academics, combined with a critical analysis of political rhetoric and media discourse, this report meticulously deconstructs the manufactured controversies used to discredit the Convention. It brings into sharp focus the pervasive and tragic crisis of femicide and gender-based violence in Türkiye, which constitutes the real, life-threatening problem the Convention was designed to combat. Furthermore, the report chronicles the powerful and resilient resistance from civil society and documents the tangible, detrimental effects the withdrawal has had on legal protection mechanisms for women and other vulnerable groups. The analysis concludes by assessing the challenging future of the fight for women's rights in a post-Convention Türkiye, highlighting the remarkable resilience of advocacy efforts and reaffirming the enduring relevance of the principles the Convention champions.

1. Introduction:

A Landmark Treaty Abandoned

The Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, or the Istanbul Convention, stands as the most comprehensive international treaty designed to tackle violence against women. Opened for signature in Istanbul in 2011, it represented a gold standard, a roadmap for legal and social reform to ensure women could live free from violence. Türkiye, hosting the signing ceremony, took pride in being its first signatory and, in 2012, the first country to ratify it, embedding its principles into the national consciousness and legal framework.

A decade later, in a move that sent shockwaves across the globe, Türkiye became the first and only country to withdraw from the treaty. The decision, announced via a midnight presidential decree on March 20, 2021, was not just a reversal of policy; it was an act that sought to erase a decade of progress and silence a vibrant discourse on women's rights and gender equality. This report, "Erased from the Scene," investigates the context, causes, and consequences of this withdrawal.

This paper posits that Türkiye's departure from the Convention was the result of a protracted and deliberate political campaign that successfully manufactured a moral panic. By distorting the Convention's text and purpose, opponents created a set of "invented problems," claiming the treaty undermined the family, promoted "gender ideology," and encouraged homosexuality, to obscure the "real problem": the staggering levels of violence against women that the Convention was effectively beginning to address. Through an analysis of interviews conducted with lawyers, academics, and activists, alongside a review of media reports and public discourse, this report will trace the journey from ratification to withdrawal. It will demonstrate the Convention's vital importance to the Turkish legal system, document the societal fallout of its abandonment, and chronicle the powerful resistance that rose to defend it.

2. The Istanbul Convention:

A Comprehensive Framework for Protection

To understand the gravity of the withdrawal, one must first understand the Convention itself. It is not merely a symbolic document but a legally binding instrument that obligates states to act.

2.1 The Four Pillars:

Prevention, Protection, Prosecution, and Co-ordinated Policies

The Convention's strength lies in its holistic, four-pronged approach:

Prevention: Requiring states to challenge gender stereotypes, promote equality in education, and train professionals to identify and prevent violence.

Protection: Mandating the establishment of shelters, 24/7 hotlines, and specialist support services for victims. It also requires that restraining or protection orders are made available and enforced.

Prosecution: Ensuring that all forms of violence against women are criminalized and that perpetrators are brought to justice. It removes "culture, custom, religion, or so-called 'honour'" as justifications for criminal acts.

Co-ordinated Policies: Obligating states to adopt a comprehensive and coordinated approach, involving all relevant state agencies, NGOs, and national parliaments in the effort to eradicate violence against women.

2.2. Türkiye's Historic Role

To discuss Turkey's case historically, it is important to mention the case of Nahide Opuz. Nahide Opuz is a Turkish citizen who consulted to ECHR (the European Court of Human Rights) after many times she claimed protection from state related authorities but ended up receiving violence and threats constantly from the perpetrator, her ex-husband. Nahide Opuz and her mother were victims of severe and repeated violence by Nahide’s ex-husband—he ran them down with a car, stabbed Nahide seven times, and ultimately shot and killed her mother in 2002. Despite their appeals to the authorities, Turkish law enforcement and prosecutors repeatedly failed to effectively intervene. Violations found by the European Court of human rights were right to life, prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment, and non-discrimination. There are two important assertions of the courts. One of them was “domestic violence constitutes gender-based violence that is a form of discrimination against women”. The other is that “the court emphasized that domestic violence is not a private matter but a public interest concern requiring effective state action.”

It is important to mention Nahide Opuz’s case because an international court was constantly pointing out the abnormal positioning of police officers as referees in the case which were in the first place responsible for the protection of the victim. It is to say that this case and the reputation of Turkey were the basis for a claim to an International Convention. Turkey should have taken some responsibility both in social and legal arena after that bad reputation it gained universally. On the other hand, gender-based violence was a crucial reality for Turkey and an immediate action was necessary. The political action of Turkey to sign the Istanbul convention should have followed actions that are concerning rights for women, safety for women but we continually see an upside-down reality. In every case where there is a woman violated or murdered it is still the case that violence is not a private matter. The publicity, the importance of state protection is still the case but the conservative voices are constantly claiming otherwise and prioritizing other values as if protecting women is a value rather than a necessity. “…many conservatives viewed the Convention as a threat to traditional family values. They believed it undermined the role of the family and portrayed men as potential criminals simply because of their gender. Over time, even some people who supported the Convention began to feel that their cultural values were being questioned or attacked, largely because of the strong criticisms coming from conservative voices.” (Çayır, 2025) Therefore, it is important to remember the historical and epistemological background of the convention to remember the real problem, the real struggle. For further implementations to a research like this, we need to underline that protecting women is not a threat for any cultural value; it must be the core priorities of any culture that human kind lives in.

2.3 The Significance of "Gender"

The Convention defines "gender" as "the socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for women and men." This definition acknowledges that much of the violence against women is rooted in unequal power dynamics and harmful stereotypes, not biological differences. Opponents twisted this into an assertion that the Convention was importing a foreign "gender ideology."

Pointing out gender as an ideology rather than something to discover and blend it with what future generations bring to the system of thoughts was just an act of demonizing it. Historically, people in general are most afraid of the unknown. So that making something not questionable, silencing the crowds that are questioning and exploring is the best way to increase the fears against it. Throughout our analysis in this research, we have discovered that there are metanarratives upon both the gender as a term and also the convention itself that successfully cover up the real struggle and the problem behind them.

3. The Turkish Context:

The Necessity of the Convention

The Istanbul Convention was not an abstract legal document for Türkiye; it was a desperately needed tool to combat a deep-seated social crisis.

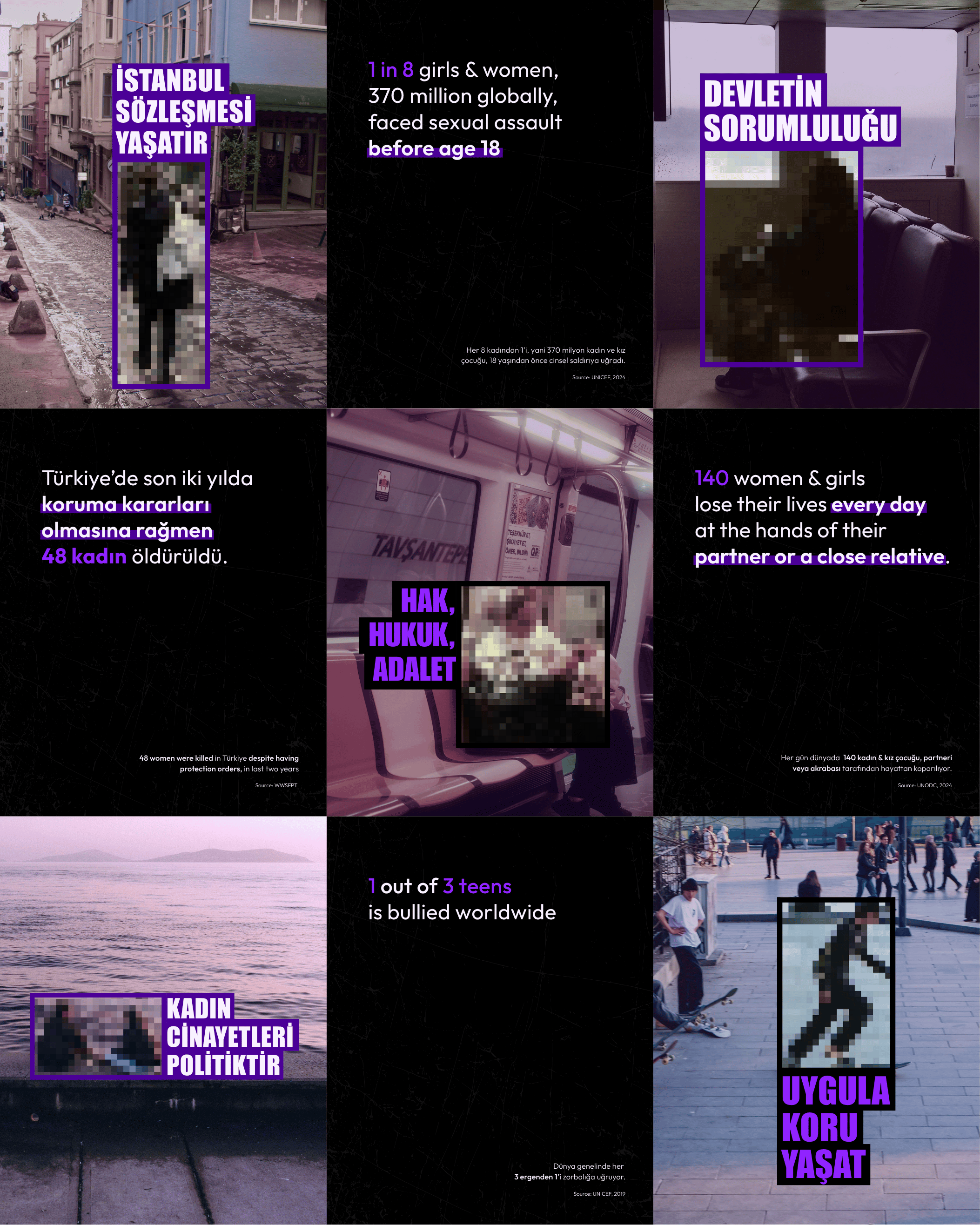

3.1 The "Real Problem": A Crisis of Femicide and Violence

Data from organizations like the "We Will Stop Femicide Platform" (Kadın Cinayetlerini Durduracağız Platformu) consistently paint a grim picture of hundreds of women killed by men, often partners or relatives, every year. Beyond femicide, rates of domestic abuse, sexual assault, and harassment remain alarmingly high. The Convention provided a clear mandate for the state to collect data, provide services, and, most importantly, send a clear message that such violence would not be tolerated.

3.2 Voices from the Legal Frontline: The Convention in Practice

Interviews conducted for this project with lawyers who specialize in women's rights reveal the tangible impact of the Convention in the courtroom. A key principle that gained traction through the Convention was that "the woman's statement is the basis" (kadının beyanı esastır) for initiating an investigation. This was not, as critics falsely claimed, a mechanism for imprisoning men without proof. As one lawyer explained:

“Sexual assault often happens in secret, between two people, and evidence is not always available. The principle of accepting the woman's statement as the basis is for initiating an investigation before moving to the evidence stage. This does not mean the man is immediately jailed. It means the prosecutor starts an investigation based on her complaint. In our country, women who are under pressure already think three or five times before speaking out, because they could be ostracized or even killed.”

This principle was crucial for overcoming the evidentiary hurdles in domestic violence cases and ensuring that victims were not dismissed at the outset. Lawyers confirmed that the Convention empowered them to argue for more robust protective measures and to hold state institutions accountable when they failed to act. While the Convention did not introduce new formal responsibilities for lawyers, it did provide a normative framework for a more empathetic, rights-based approach. Legal professionals are encouraged to adopt a gender-sensitive lens, recognizing that violence against women is both a legal and social justice issue.

Its withdrawal has created a palpable chill, emboldening perpetrators and creating uncertainty within the judiciary. “…the Istanbul Convention was not only about law; it was about recognizing structural violence. Its withdrawal was a regression, both symbolically and materially. By protecting a patriarchal and capitalist system under the guise of tradition, the Turkish government sends a clear message: some lives matter less than others.” (Durafour, 2025)

4. The Politics of Withdrawal:

Manufacturing a Moral Panic

The campaign against the Istanbul Convention was a masterclass in political disinformation. It systematically reframed a human rights treaty as a threat to the nation's moral fabric.

4.1 The Rise of an Opposition Narrative

Beginning around 2018, a coalition of conservative, ultra-nationalist, and religious groups began a concerted attack on the Convention. They argued that its provisions were a Western import, incompatible with Turkish family values. This narrative gained traction within segments of the ruling party and its allied media, transforming a fringe complaint into a mainstream political debate.

4.2 Deconstructing the "Invented Problems"

The opposition's case rested on a series of deliberate misinterpretations:

"The Convention Destroys the Family": Critics claimed that by making it easier for women to get restraining orders, the Convention was breaking up families. This argument ignored the reality that the "families" being "broken up" were often sites of life-threatening violence.

"It Promotes Homosexuality": This claim centered on the Convention's non-discrimination clause, which states that its protections must be secured without discrimination on any grounds, including "gender identity or sexual orientation." This standard anti-discrimination language was twisted into an assertion that the Convention was actively "promoting" LGBTQ+ identities, a narrative that tapped into rising homophobic sentiment.

"The Concept of 'Gender' is a Threat": As discussed, the sociological definition of gender was portrayed as a radical "ideology" being forced upon Turkish society. The feeling of being threatened and the notion of fear are often the biggest political strategies to control people’s approach to the convention. (Çayır, 2025)

These metanarratives created a potent, albeit false, narrative that pitted the Convention against the Turkish nation, its religion, and its family structure.

4.3 The Role of Media and Political Discourse in Amplifying Disinformation

Pro-government media outlets played a crucial role in this campaign, giving disproportionate airtime to anti-Convention voices and relentlessly repeating the same false claims. Columnists and television commentators framed the debate as a matter of national sovereignty versus foreign imposition. This created an echo chamber where the "invented problems" were presented as fact, while the voices of women's rights defenders were marginalized as agents of foreign influence. As documented in the article "The Politics of Control," the issue became a tool for political consolidation, a way to rally a conservative base around a common enemy.

5. Societal Impacts and Civil Resistance

The withdrawal was not a clean break. Its announcement triggered a fierce backlash from civil society and has had a chilling effect on the ground.

5.1 The Chilling Effect on Legal and Social Protections

Türkiye's 2012 ratification of the Convention was followed by the passage of Law No. 6284 to Protect Family and Prevent Violence against Women. This law is a direct domestic reflection of the Convention's principles, providing the legal basis for restraining orders, shelter access, and other protective measures. For years, the Convention and Law No. 6284 worked in tandem, providing a powerful legal shield for women. The Convention gave domestic law international backing and a clear framework for implementation.

While Law No. 6284 remains in effect, its foundation has been critically weakened. Lawyers report that some judges and police officers, feeling empowered by the political climate, are more reluctant to issue and enforce restraining orders. Victims of violence feel less confident that the state is on their side. The withdrawal has sent a powerful message of impunity to perpetrators: the state's commitment to protecting women is no longer unequivocal.

5.2 The Resilience of the Women's Movement

The decision to withdraw was met with some of the largest women's protests in Türkiye's recent history. Tens of thousands of women and their allies took to the streets in cities across the country, chanting, "We will not give up the Istanbul Convention!" (İstanbul Sözleşmesi'nden vazgeçmiyoruz!). Women's rights organizations filed lawsuits challenging the legality of the withdrawal, arguing that a presidential decree could not override a law ratified by Parliament. Though these legal challenges were ultimately rejected, the resistance demonstrated the deep roots the Convention had put down in Turkish society.

5.3 V for Human and The "Empty Seats" Campaign: A Symbol of Defiance

V for Human, originally comes from the movie V for Vendetta. The core message in the movie was what is necessary is first individual awareness and then collective action. This is also what we try to do starting from ourselves: gaining awareness in many aspects, learning from each other and then discovering what we are able to do as a collective whole. The idea behind an organization like this was firstly designed for rooting for women’s rights but as we started to do research, events and get together, we understood that what women’s rights also goes with human rights. We wanted to be more inclusive; we wanted our name to represent what we claim by our actions and efforts. Therefore, we’re proudly asserting that V for Human stands for human rights for all who seek for. It is fair to mention that the Istanbul Convention is also standing for those who need a greater protection and inclusive approach both socially and legally.

In the wake of the withdrawal, advocacy has adapted. As part of this project, we launched the "Empty Seats" initiative as a direct response to a worrying trend: the normalization of data related to domestic violence and femicide. We noticed that as the statistics grew, they were becoming just another set of numbers. Our campaign was therefore designed to bring back the frontier cases, humanizing the data by highlighting the individual backgrounds and erasing lives behind each statistic. However, while conducting this social media campaign, it became clear how deeply entrenched the counter-perspective is within its own media echo chamber and how difficult it is to break through. This experience has led to the identification of a crucial next step: conducting research and development on how to effectively communicate with this targeted audience. Without new strategies, there is a risk that awareness and educational campaigns will also fall into their own advocacy echo chamber, failing to reach those who need to hear the message most. The campaign's symbolism, marking the empty space left by the Convention's protections, serves as a constant, visual reminder of what has been lost. It is a statement that while the government may have withdrawn, the seat of responsibility remains, and civil society will continue to hold them accountable to it.

6. Conclusion: Rethinking the Data, Reaffirming the Cause

Türkiye's withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention was a profound setback for human rights. It was a political act, driven by a cynical campaign of disinformation that preyed on social anxieties and targeted the most vulnerable. The data collected and the voices chronicled in this report lead to an undeniable conclusion: the justifications for withdrawal were baseless, while the need for the Convention was, and remains, a matter of life and death for women in Türkiye.

The "invented problems" of threats to family and tradition were a smokescreen for the "real problem" of a patriarchal system that resists accountability for the violence it perpetuates. The withdrawal has not solved any problems; it has only exacerbated the danger faced by millions and damaged Türkiye's international standing.

Yet, the story does not end with withdrawal. The fierce, creative, and unwavering resistance from the Turkish women's movement and its allies demonstrates that the principles of the Istanbul Convention cannot be so easily erased. The fight for its reinstatement, and for the full implementation of Law No. 6284, continues. The struggle is no longer just about a treaty; it is about the very soul of the nation and its commitment to the fundamental right of all citizens to live in safety and with dignity. The seat may be empty, but the watch is not over.

7. References

Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention).

Çayır, Ş. (2025, July 22). The Role of Societal Legitimacy in Policy‑Making Processes: A Discussion About Affective Politics. V FOR HUMAN.

Durafour, N. (2025, July 25). The Politics of Control: Gender, Power, and the Legacy of the Istanbul Convention in Türkiye. V FOR HUMAN.

Law No. 6284 to Protect Family and Prevent Violence against Women (Türkiye).

Publicly available reports and data from We Will Stop Femicide Platform (Kadın Cinayetlerini Durduracağız Platformu).

Interights. (n.d.). Opuz v Turkey. Interights.

Council of Europe. (n.d.). The landmark judgment that inspired Europe to act on violence against women.

Report Colophon

This report is the primary output of the "Seyirden Silinenler" (Erased from the Scene) project by the V FOR HUMAN (V4H) Association. V4H is a non-governmental organization dedicated to advocating for human rights through intellectual activism. Digitally published in Istanbul, Türkiye, in August 2025 at vforhuman.org/publications.

Project Team & Contributors

Legal Research & Analysis: Esma Kassap, Natacha Durafour

Sociological Research: Şevval Çayır

Project Coordination: Deniz Sulmaz

Visual Design & Communication: Parthivi Dutta, Leah Benjamin

Suggested Citation:

V FOR HUMAN (V4H) Association. (2025). Erased from the Scene: Türkiye’s Withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention.

Contact Information:

For inquiries regarding this report, please contact: hi@vforhuman.org

Follow our work on Instagram: @vforhuman

Learn more about V4H at vforhuman.org

Copyright © 2025 V FOR HUMAN (V4H) Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. V4H encourages the dissemination of this report for advocacy and educational purposes. For permissions and inquiries regarding broader use, please contact us; we are readily available for communication.